I’ve worked with a lot of organizations who are somewhere along their journey toward agility. Many of them talk about the cultural challenges they face in helping their organization, teams, and people to change. But discussions about culture can be vague and unsatisfying, like talking about the weather; everyone always has something to say about it, but no one seems to be able to do anything to change it.

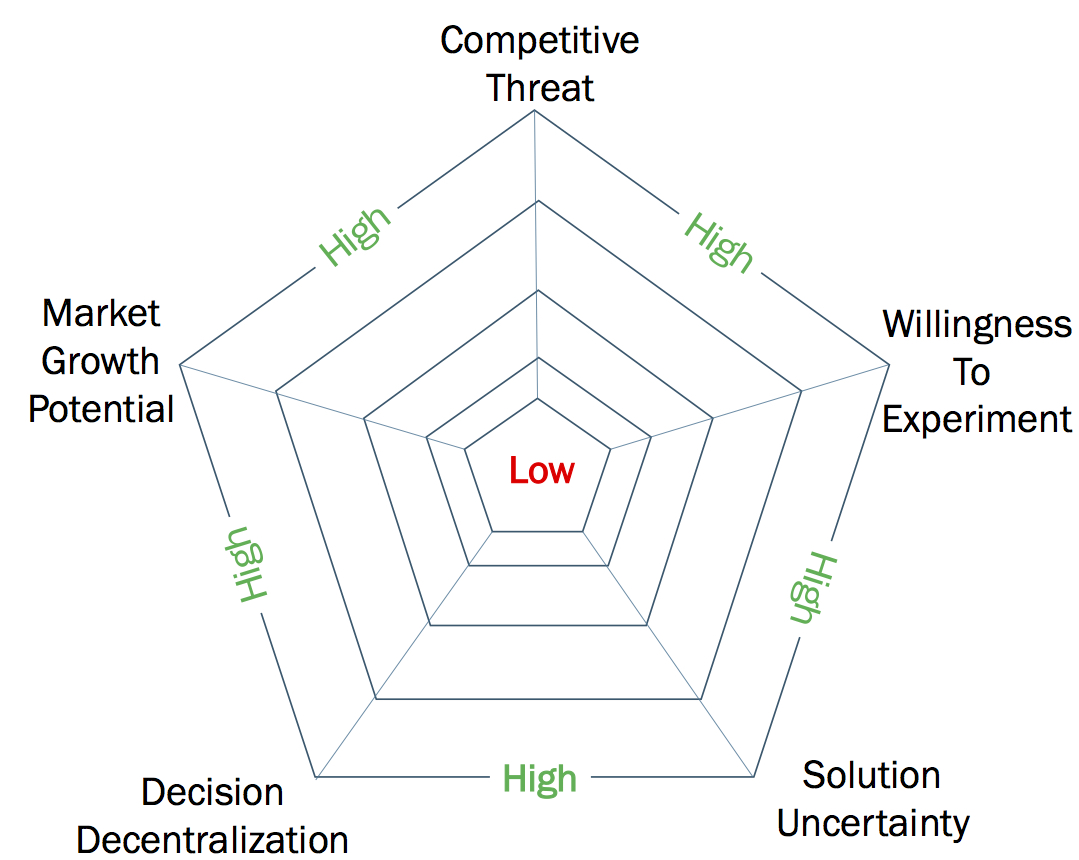

I have created a little exercise that I like to use to help focus on things we can change, or at least situations to seek out or avoid, to help focus change efforts. The essence of it is summarized in a picture (see Figure 1). I call this the agile affinity model, and the dimensions the key drivers of empiricism. This is one of the exercises we use in our Professional Agile Leadership-Essentials class to help managers better understand where agility fits and where it may help their organization.

Figure 1 The Agile Affinity Model considers 5 key drivers that influence attraction or resistance to empiricism

The Key Drivers of Empiricism

These dimensions express different forces, both internal and external, that affect the way people think about agility. By agility, I mean the use of an empirical approach to incrementally deliver business value, measuring the effect of that delivery, inspection of the results, and adaptation based on learning from inspection. Each of the dimensions are described below.

Competitive Threat

The competitive threat dimension expresses the degree to which the product is challenged by competitors.

|

Indicators |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

High market share |

Low market share |

|

Few competitive alternatives |

Many competitive alternatives |

|

High customer lock-in |

Low customer lock-in |

Willingness to Experiment

The willingness to experiment dimension expresses the degree to which the organization is comfortable with planning uncertainty.

|

Indicators |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

Increasing plan detail when uncertainty increases |

Forming hypotheses and running experiment to test assumptions when uncertainty increases |

|

Adding more milestones and reviews when uncertainty increases |

Planning in small increments, measuring, then inspecting and adapting to revise plans |

|

Deviations from plan are regarded as negative outcomes |

Deviations from plans are regarded as simply new information |

Solution Uncertainty

The solution uncertainty dimension expresses the degree to which the organization believes that they are certain about what the market or customers need.

|

Indicators |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

Planning approach in which change requests are regarded as negative outcomes |

Running frequent focus groups to assess customer needs and reactions to alternatives |

|

Little actual customer usage data available |

Instrumenting applications to obtain actual usage information |

|

Release plans largely track to product roadmaps |

Running A/B tests to test or validate product ideas |

|

Detailed product roadmaps extended several releases into the future |

Lack of long-term product roadmaps, or having product roadmaps that change over time |

Decision Decentralization

The decision decentralization dimension expresses the degree to which decision-making authority is dispersed in the organization, in which certain specified decisions can be made by individuals or teams without having to seek approval from managers.

|

Indicators |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

All spending decisions must go through a manager with appropriate budgetary authority |

Allowing teams to be responsible for a budget they can spend however they see fit to help them deliver on their goals |

|

All hiring and firing decisions are made by a manager |

Allowing teams to make hire/fire decisions without seeking manager approval |

|

All product decisions are made by management |

Allowing teams (including Product Owner) to make product decisions |

Market Growth Potential

The market growth potential dimension expresses the degree to which the product has growth potential in its market, or the degree to which it can significantly grow revenues.

|

Indicators |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

The product is in a market that is contracting |

The product is in a market that is rapidly expanding |

|

The product’s market share is shrinking |

Dominant competitors are weak and losing market share |

|

The product is a “cash cow” |

It is possible to increase product revenues by growing absolute numbers of customers or by growing market share |

Why These Dimensions?

The dimensions reflect different forces that affect the beliefs and values in an organization. The two external dimensions (competition and market growth) balance the internal forces (willingness to experiment, solution certainty, and decision decentralization). The external dimensions reflect the things that often attract organizations to agility, and the internal dimensions reflect the beliefs that often prevent organizations from becoming more agile. These dimensions capture the essence of challenges that organizations face, and provide a useful way to gain insight into attitudes and have discussions about what people might be able to do to change those beliefs.

The model is intended to bring to the surface assumptions that may be unspoken but important or to cause people to think about the environment in which they are considering introducing an agile or empirical approach. There are no “right answers”, and you should be careful not to steer the group toward a particular answer.

The model is normally used in a group exercise. You might have a group of people from the same organization, or you may have people from different parts of the same organization, potentially working on different products. You may even have people from different companies if you were using this in a public workshop.

If the group is large, divide up into smaller teams of no more than 5 people, potentially along product lines, if they work in the same company. Have each team plot each dimension for the product/team they work on. If there are people from different products in the same team, have them plot each product. Draw lines between the dimension scores, using a different color for each product. The result might look something like Figure 2.

Figure 2 Different products will plot differently on the affinity dimensions

Interpreting the Results

There are no “right answers”; the value in the exercise is to stimulate a discussion about the challenges each product organization or team may face in adopting an agile/empirical approach, and to get them to think about what they may need to do in response. I have each team go through their scorings and explain what led them to their conclusions. During this discussion, it’s important that whoever is leading the exercise, as well as the other workshop participants, just listen and ask clarifying questions. After everyone has presented, you’ll want to help the group draw some conclusions. Some common discussion points are presented below.

Low Competitive Threat or Market Growth Potential

When a product scores low in Competitive Threat, or Market Growth Potential, it’s worth discussing why that product would benefit from empiricism. If there isn’t much threat, or there isn’t much opportunity, maybe the organization should focus on products that have a greater need. Some organizations have come to see agile as the way they want to run everything, but that’s not very thoughtful. Most organizations can only really support so much change, and forcing a change that won’t produce much benefit is probably depriving some other team from getting the help it needs.

High Competitive Threat or Market Growth Potential

When a product scores high in the Competitive Threat, or Market Growth Potential, but low in other areas, they have opportunities with which empiricism could help, but they have internal barriers that may prevent them from working empirically.

Low Solution Uncertainty

Low Solution Uncertainty may sound like a good thing, but it’s generally not. The organization may believe that it knows what customers want, but if it’s not measuring customer experience it really doesn’t know. As a result, it may be missing opportunities to better serve those customers. The first step is to start measuring customer experience to see how many of its beliefs are actually true.

Low Willingness to Experiment

Low Willingness to Experiment often arises from an aversion to making mistakes in a “high fear” environment. It may also reflect a belief that increasing planning precision increases the likelihood that the plan will be correct. In these organizations, plans are regarded as “the gold standard” and any deviations from the plan are considered to be the result of poor execution. More often, the reality is that the assumptions behind the plan were not realistic.

Increasing the willingness to experiment takes time, and running lots of small experiments. Making small experiments is a lot less costly and disruptive than making big plans that often go wrong. Eventually, people realize that big plans were actually part of the problem, all along.

Low Decision Decentralization

Low Decision Decentralization reflects a lack of trust between managers and team members. There are a variety of ways to work through this, provided that both sides are willing, and they generally center on the managers gradually giving teams more decision-making authority over small things, then working up to bigger things.

Once you’ve discussed the differences, a good next step is to ask each team if they are happy with where they are today? Is their current approach working? Chances are it isn’t, since they are in a workshop that is usually part of a broader improvement effort. If they do want to improve, you can use their example to have a discussion with the overall group about what things they might do to improve in that dimension. The point is for them to come up with their own action plan of things to try.

Not only are organizations different from each other, but different part of the same organization can be quite different. Everyone starts from a different place and has different goals, which is why there is no “one size fits all, or even most” approach to adopting agile practices, or to scaling them. Different people will look at empiricism and agility differently. Not everyone sees the same need, and not everyone has the same goal. Helping them feel that it’s ok to find their own way is an important step toward self-organization.

Helping people better understand their own need for empiricism and attitudes toward empiricism helps them to leave behind the “we need to become agile (whatever that is)” mindset and start to really understand what empiricism will do for them, and what they will need to change to reap its benefits.