In business, the quest for predictability is universal. We all want to grab hold of the reality we face everyday and, somehow, bend it to our will. When we are surprised by the unexpected, we often assume that we have failed in some way. We have this underlying belief that if we just do our job well enough, we can prevent any and all surprises and that success will follow. Unfortunately, that’s nothing more than a nice fairy tale.

In real life, we have no hope of overcoming all uncertainty — zero. Instead, we must begin to accept it and learn how to operate, even thrive, within it. But we can’t do any of that if we don’t try to understand it. Stephen Bungay, the author of The Art of Action, helps us understand the shape of our uncertainty by expressing it via something he calls “the three gaps.”

These gaps are places where uncertainty shows up:

The Knowledge Gap: the difference between what we’d like to know and what we actually know.

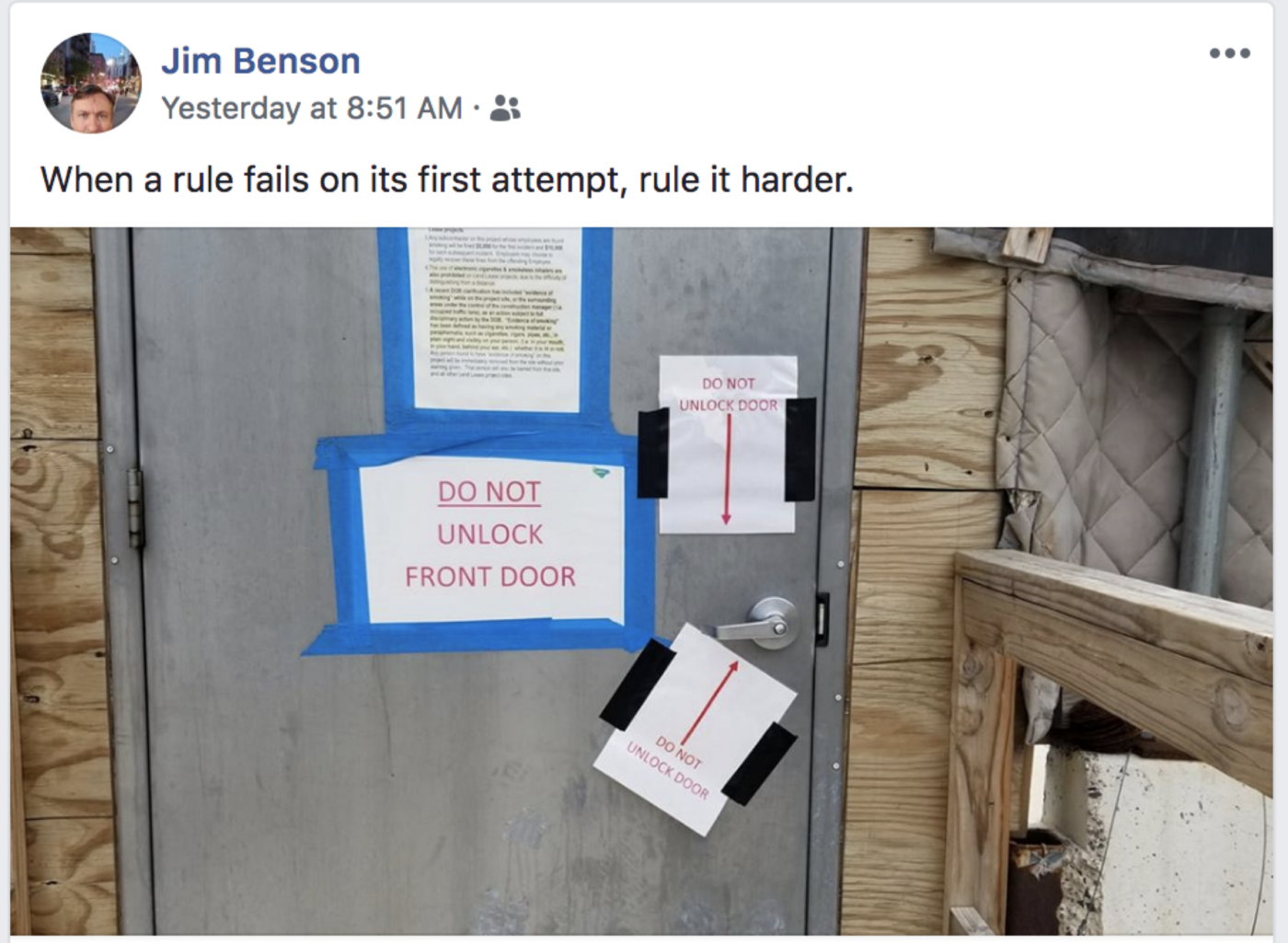

This gap occurs when you’re trying to plan, but often only manifests when you are trying to execute the plan. Often, we try to combat this gap, not by doing something different than before, but by doubling down on what we’ve already done. In other words, we just didn’t do it well enough the first time. So, instead of accepting that we may never know everything we’ll need to know up front, we double down on detailed plans and estimates.

The Alignment Gap: the difference between what we want people to do and what they actually do.

This gap occurs during execution. Like with the knowledge gap, we try to fix it by doubling down. In this case we double down on providing more detailed instructions and requirements. We are quite arrogant in our thinking and believe that if we can just be more thoughtful and more detailed, we can prevent all surprises.

The Effects Gap: the difference between what we expect our actions to achieve and what they actually achieve.

This gap occurs during verification. We don’t often consider that, in a complex environment, you can do the same thing over and over and get different outcomes despite your best efforts. Instead, we think we just didn’t have enough controls. We are stubborn to the point of stupidness and continue to think that we can manage our way to uncertainty.

The ugly truth

By reinforcing the idea that you can control your way to certainty, you aren’t teaching people how to be resilient and how to operate despite what comes their way. This means that when surprises do sneak through, people will be woefully unprepared and, more often than not, efforts will start to veer towards blaming the responsible party instead of figuring out a way forward.

The ugly truth that we all must face is that, in complex environments like software development, healthcare, social work, product development, marketing, and more — we will never defeat uncertainty. To be honest, we wouldn’t like what would happen if we did. It would be the end of learning and innovation.

So, what now then?

While we have to accept that some uncertainty will always remain, we can try to tackle the low hanging fruit. For instance, we don’t abandon all research or planning. We just accept that things may not always go to plan and have an idea of how we’d react when uncertainty pops up.

When I managed the web development team for NBA.com, we would run drills for our major events like the Draft and walk through scenarios like “What happens if a team drafts someone we don’t have a bio for?” and “What will we do if our stats engine breaks down?”We accepted that because we can’t control everything, the skill that we really need to survive in business is resiliency. We needed to learn to anticipate, react and recover. We learned how to think about resiliency and build it into our work processes, not just our technical systems.

So, if you are finally getting to the point of accepting that you can’t conquer uncertainty, the next mission is to begin to build the skills of resiliency. There is no comprehensive list of ways to become resilient but I’ll share a few things I use while working in an uncertain environment.

The Agile Manifesto

The Agile manifesto is an excellent embrace of uncertainty and a pushback against our natural tendencies when reacting to Bungay’s three gaps.

While there is a place for plans, documentation, contracts, and processes they are not the only, or even most important, things we need to excel in uncertain environments.

The Scrum Framework

One of the biggest benefits to the scrum framework is that sprints act as a forcing function to work in small batches. If you work in a smaller batch you notice the gaps more quickly and, if you fall prey to those natural tendencies to double down on instruction and planning, you’ll do so in a smaller way and, hopefully, learn more before the next piece of work starts.

This is a perfect example of accepting uncertainty and trying to limit the potential damage.

Kanban and Limiting Work-In-Progress

Adopting Kanban forces you to limit the amount of work going on at one time. This has a similar benefit to the Scrum framework, but at an even more granular level. While Scrum limits how much you start in a Sprint, Kanban limits how much you have in progress at any one time.

Thinking of your work-in-progress in economic terms can really help you understand the value of limiting it. My friend and generally awesome person, Cat Swetel, once said that you can think of your work falling into three buckets:

- Options — work not started

- Liabilities — work in progress

- Assets — work already finished

It is in our liabilities that we are subject to the effects of uncertainty. If we limit the potential impact to a manageable amount, we limit the possible damage and, more often than not, we turn liabilities into assets faster.

Probabilistic forecasting

Often, even though we know there are many potential outcomes, we still provide a single forecast. A better way, that visualizes existing uncertainty, is to give forecasts AND state the likelihood that a particular forecast will occur. You’re very familiar with this whether you realize it or not. Every weather forecast you’ve seen uses this approach.

Doing this is easy. You can use your historical data to forecast probable outcomes with cycle time scatterplots (for single items) or monte carlo simulations (for a group of items).

Wrapping it up

No matter what you choose to do going forward, by far the most important choice you can make is to accept the inevitability of uncertainty and to commit to learning how to thrive in the face of it.

Sharing stories of your successes and failures helps both yourself and those who hear or read them to widen their perspectives. Having to tell the story makes you synthesize the information and make conclustions so that you understand what happened enough to tell the tale. And, while your context will not likely perfectly match that of your readers or listeners, it may provide them perspective and information that they can incorporate into their hypotheses.