If you give a developer a verbal warning for surfing social media all day, you are crushing their autonomy. Insisting on core hours of 10am-4pm violates self-organisation. Personal development plans are so PRINCE II. Right?

Well, maybe. On the other hand, having someone relatively experienced and influential on your side, to help shape your career and keep you off the annual redundancies list might actually be quite useful.

Here are four case studies of line management observed with real agile teams; some effective and some problematic. Hopefully this should help you to consider how to make your own HR practices supportive of great software product delivery.

The irresistible force (Scrum) meets the immovable object (HR promotions policy). Who will triumph?

A development team in online retail is doing pretty well. They are well on track to upgrade their eCommerce system to a modern and well-architected system, and they have established a collaborative technical community across the other half-dozen teams that build the site. Life is good for 11 months of the year, but then the annual ritual swings round again that causes the development team to focus on individualism, job titles, and elusive 2% pay rises. This year, two members of the team feel that it is their time for a promotion. They fill in all the right paperwork, their line manager supports their application at the big review meeting; but to no avail. The feedback is:

Standards are very high, and an “associate engineer” needs to demonstrate more industry experience to be promoted to “engineer”.

It’s difficult to feed this back to the people involved; they feel hard done by and I agree with them. The team carries on over the next month or so, but they’ve lost a bit of momentum and in the corner of my eye I can’t help but notice people looking at job websites.

Issues highlighted

The promotions process in place has the following effects:

- People strive towards high professional standards (or perhaps figure out how to game the system).

- Focus is drawn towards personal development plans and paperwork in the run-up to appraisals.

- If people miss out on promotions, motivation and productivity drop.

- Staff turnover is likely to be a little higher.

What to do

Part of the role of a good scrum master is to work with organisations to help them to evaluate the policy choices they have made. It can help to put some numbers on it. Saying “people are unhappy because they didn’t get promoted” is likely to attract sympathy but little change. Saying “Our current promotions system is likely to cost the department hundreds of thousands of pounds” has a better chance of resulting in positive action.

Takeaway: Good HR practice is like good office facilities management – if it’s done well, you don’t even notice it’s happening.

The developer who is always late

A small, close-knit development team has had stability in their personnel for many years, until a new developer joins from another department. They settle in well and their technical skills quickly establish a mutual respect among the team. However, the new developer is often late, even missing the 10:30am stand-up at least once a week. After a few months of raised eye-brows and building tension, the developer in question opens up to the team about a long-term sleep condition that they have been managing for many years.

The team and the product owner (who line-manages the team) recognise this as a genuine problem and accommodate the new developer, and the team returns to a state of productivity and collaboration. Occasionally, people working alongside the team question the very visible fact of the developer’s lateness. The team are quick to highlight the much less measurable fact of the developer’s commitment to the team and the quality of their work. It’s good fun to arrive in the morning to find a 2am code check-in that solves the current technical challenge.

Things to consider:

- A flexible approach to managing people is often rewarded with commitment and loyalty.

- For skilled and creative work, the easy things to measure, such as time spent at a desk, are rarely good indicators of useful productivity.

- Ask your colleagues and leaders whether they would prefer:

- To exceed all of the organisation’s strategic objectives, but have the development team roll in at 11am, if they decide to come to the office at all?

- To have the whole dev team warming their office chairs between 08:00 – 18:00 every day without fail, with neat haircuts and shiny shoes?

Takeaway: Genuine productivity of useful, business-relevant work is the most important thing. Teams should be held to account, but only for the things that matter.

Keeping the QA manager happy

A major new product line has been initiated within an enterprise-scale organisation. All they need now is a couple of development teams to build it. Hiring external developers will help a little, but most of the people will come from within the technology department. This raises questions such as:

- Who has the right skills?

- How to limit the impact on other teams and products?

Before the skills matrix excel spreadsheet maxes out the engineering manager’s hard drive, we suggest that we help the teams put together a proposal themselves. We give an example of having done this before, helping distributed team re-allocate themselves in order to alleviate time-zone issues. It took a couple of weeks and some bottom-up leadership but it’s usually a lot less difficult than people imagine. However, the response from the engineering manager is swift:

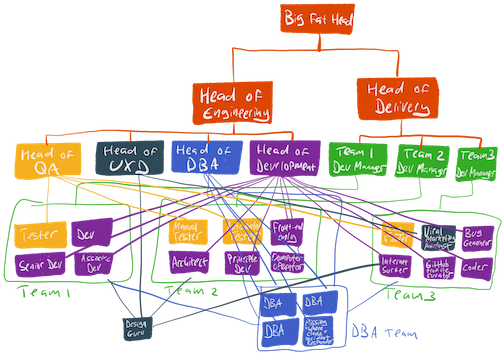

If we allow people to choose their own team, it will be impossible for the QA, UXD, DBA, and development managers to keep track of their staff!

As a result, both new and existing products were slightly compromised through delays, overheads, and sub-optimal allocation of people.

Issues highlighted

Having competency leads (QA manager, etc) should have been a great asset, leading the development of good practice and helping to establish shared standards across the department. However, in this case the competency lead roles became a constraint.

What to do

It might be difficult to make changes that affect people’s roles, but it would be negligent to prioritise maintaining an org chart ahead of forming the best possible teams to build a new product.

- Get the key people together.

- Establish some shared company-level objectives.

- Figure out the best organisational structure to achieve these goals.

Takeaway: Leadership positions should make things better, not be a constraint to work within.

The developer who doesn’t write any code

A development team working for a large public-sector agency is becoming increasingly frustrated with one of their number. The source of the frustration is a developer who has moved all around the department, and for the last three months has been a member of a Scrum team building an internal research tool. One of the characteristics of Scrum is that it is really obvious when someone isn’t pulling their weight. While the daily scrum is not intended as a reporting session or a way to micromanage the team; when a developer doesn’t complete a single task all sprint then you can’t help but ask why. Efforts by team, scrum master and product owner to encourage and support the individual have little impact. Three months later, the individual has been taken through a fair but increasingly formal performance management process, resulting in the termination of their employment. It’s hard work on all involved, but allowing the situation to continue would have been worse.

Things to consider:

- A flexible leadership style is effective, but when people do not respond and underperform then the situation must be tackled.

- It’s easier to avoid taking action, but this would have a negative effect on the rest of the team.

Takeaway: Leading agile teams is mostly exciting and rewarding, but if difficult decisions are avoided then it undermines the whole effort.

This article was originally published at Agility in Mind