Complaining is like releasing gas.

It’s a natural occurrence. Everyone does it.

But no one wants someone else to do it next to them.

We all complain. I believe branding this behaviour as a binary concept like “good” or “bad” rather than evaluating it in a spectrum doesn’t help at all.

Because both extreme ends of this spectrum harm trust. Acting like we are sublime creatures who never complain fosters artificial harmony and politics in the environment, which can easily turn into an impediment against transparency. On the other side of the coin, we take people who always complain without taking any action less seriously.

After attending a program at Oxford University discussing psychological elements of the workplace, I wanted to share some takeaways that resonate with my real-life experience about this subject.

Why we complain at the workplace has a universal root cause

Perhaps, being under pressure constantly is one of the reasons why people complain at the workplace. That’s a way to deal with stress.

To begin with, academic arguments on workplace behaviours made it clear to me that most people suffer from a universal problem that might not be fully in their control:

They work in companies in which the policy-makers treat their organisation like a machine rather than a social system.

I used “policy-makers” rather than “leaders” on purpose since I see leadership as a quality rather than a formal title or position.

Going back to the topic, the fact that “organizations are often treated like machines rather than social systems, wrongly” is not a ground-breaking revelation. There have been numerous movements (e.g. Agile Manifesto, Scrum Framework) to change this mindset and put individuals over processes from the outset.

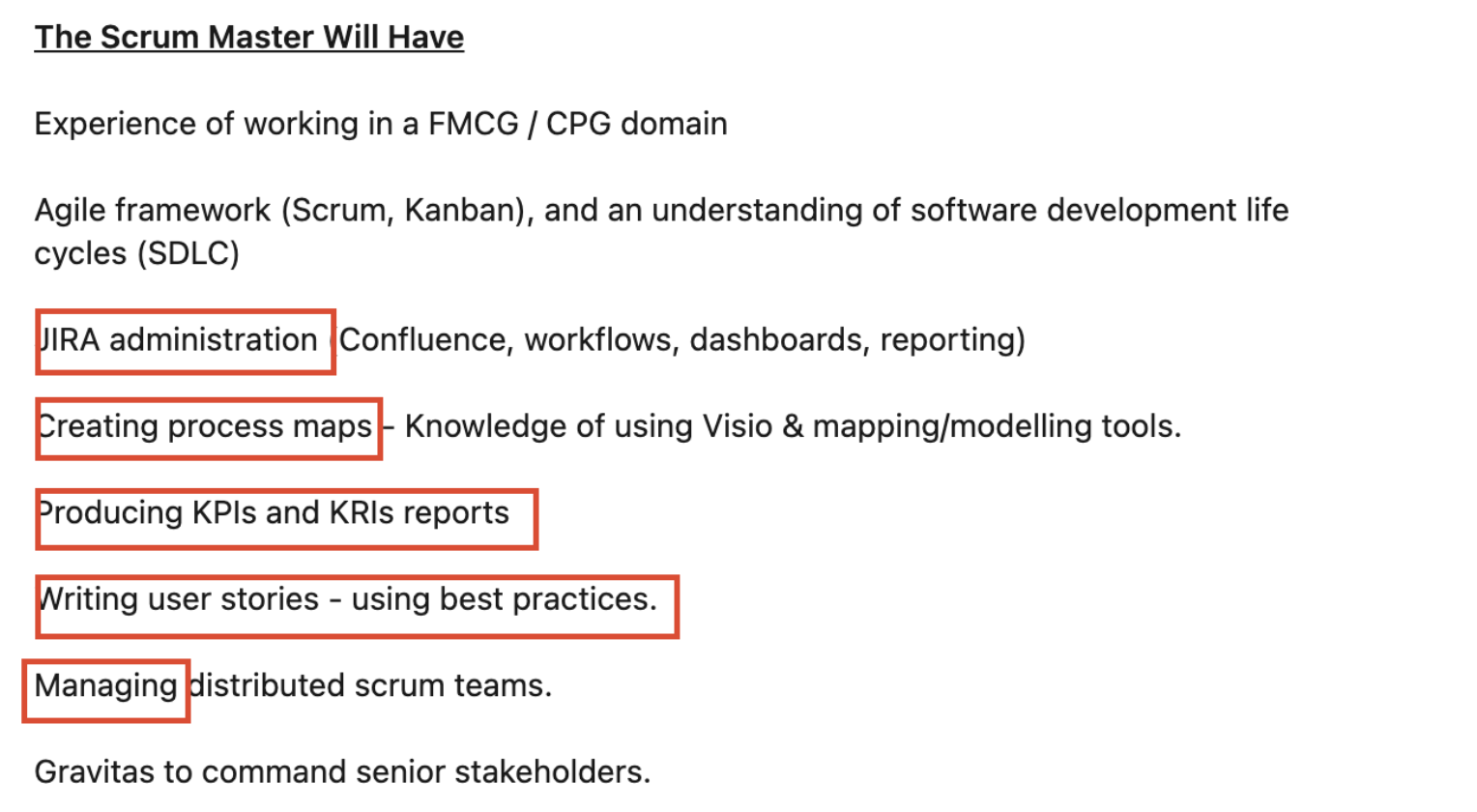

Yet, there are still tons of companies that choose to do the opposite. We often see this manifesting itself in job ads, almost comically, as an emphasis on heroism, predictive management style, and dignification of complementary practices (practices that can be helpful but are not mandatory) such as story points, user stories, burndown charts, OKRs e.g.

Thanks, but no thanks. You literally try to hire an impediment for your company.

How to take an action and make things slightly better?

Let’s take a step back. Rather than trying to save the world, we will focus on the art of the possible in this article. What is in our control in this picture? How can we complain less, improve our performance and keep our mental health intact in a social system against all odds?

First, consider there is a range of variables that influence our performance at the workplace, including, but not limited to:

- Number of working days and hours (Folkard & Tucker, 2003)

- Challenge & skill alignment (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990)

- Personality (Costa & McCrae, 1985)

- Interactions & organisational variables (Schein, 1990)

- Stress management skills (Altindag, 2020)

Compared to some other variables on the list, it would hardly be an exaggeration to assert that improving “stress management skills” is low-hanging fruit for an individual.

This journey starts with a simple step: Recognising the sources of stress.

1. Recognise the sources of stress

According to Greenhaus & Beutell conflict model, it is possible to talk about three main stress sources. Time-based, strain-based, and behaviour-based.

Please note that the original scope of the study mainly focused on family & work role conflicts. We will try to evaluate these sources in a Scrum Team context.

Time-based stress: Pressure from one work makes it impossible to meet demands from the other works. Symptoms include context-switching/multi-tasking.

Example:

As a developer, you are multi-tasking and working long hours. You think you are being treated like a machine. Furthermore, this situation results in more defects and slowed down feature delivery (and eventually even more working hours).

Strain-based stress: The person has enough time, but the strain produced by one engagement reduces the energy resources and makes it difficult to fulfil other requirements.

Example:

As a Product Owner, you think you are frequently asked by the management to produce non-value-adding reports to manage stakeholder expectation. This consumes your cognitive capacity that could be used for more valuable activities. You feel unsupported and lonely.

Behaviour-based stress: Put simply, this type of stress comes from role conflict or perceived accountability conflict.

Example:

As a Scrum Master, you are asked to monitor and report the velocity of the team to the management. You think that this demand conflicts with the expected behaviours from a Scrum Master and can hurt the organisation in the long term. You lose confidence or build a cognitive dissonance.

2. Accept your limits

Digest this fact: You are one person who does one thing at a time.

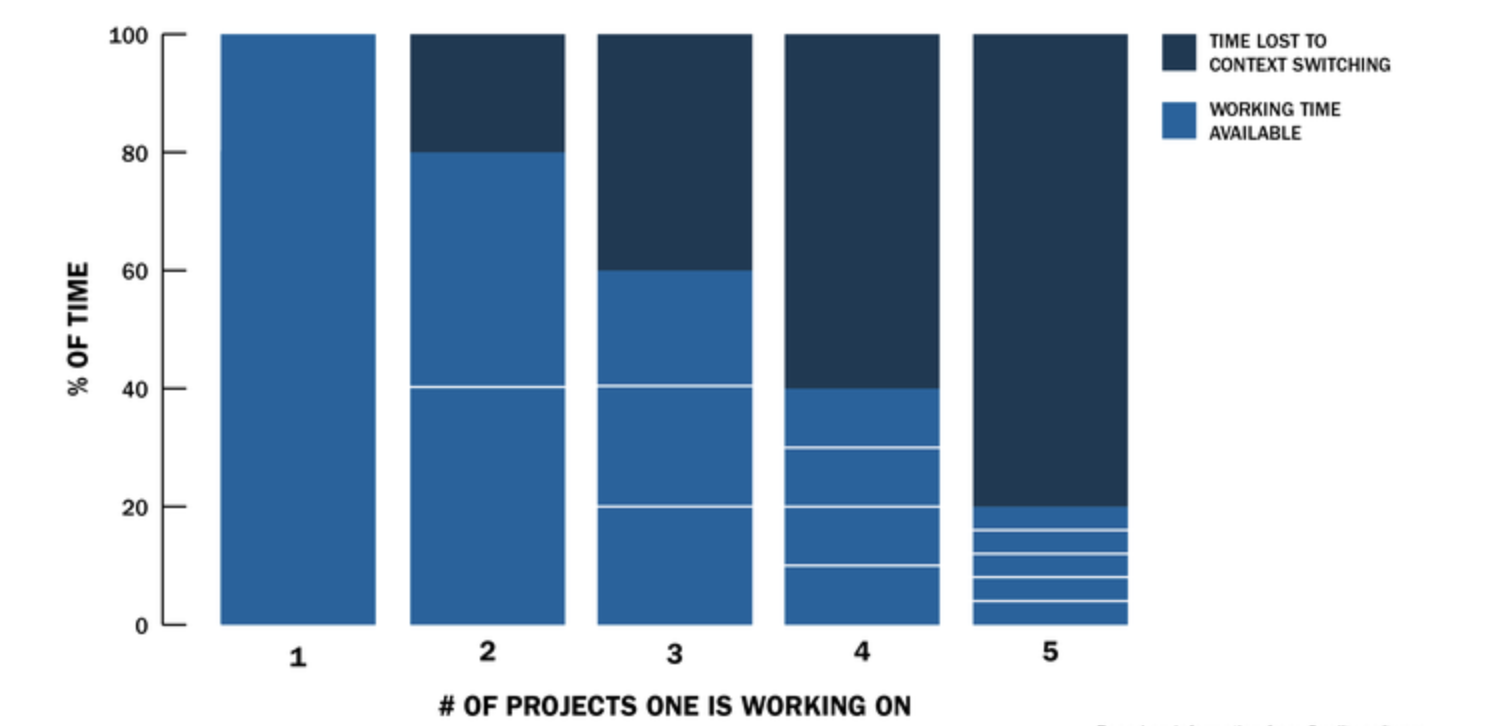

Each extra task you switch between eats up around 20% of your overall productivity.

Weinberg, G, Quality Software Management: Systems Thinking, p284, 1991

However, this information won’t be helpful by itself unless you recognise that humans usually are responsive to the expectations of people around them, perhaps more so than financial incentives (Schein, 1988). Thus, some human behaviours can change only when other people’s behaviours change.

For instance, if you see other team members making unrealistic commitments to keep their boss happy at the cost of making harm to the organisation and its customers in the process (ask Cyberpunk), you may fall into the trap of doing the same thing due to peer pressure, which takes us to the third point.

3. Use professionalism as a compass and learn to say no

Say “no” to things you shouldn’t do and/or you can’t achieve within the professional quality boundaries. Do no harm. Sometimes you do harm by saying “yes” for gaining short-term comfort.

If you were a doctor and your patient wanted you to skip washing your hands before the surgery since she is in a hurry, you would definitely say no to her.

You have limited control over what other people do, but you can still positively impact the environment by controlling your own behaviours and leading by example.

Don’t be apologetic for trying to do the right thing, but collaborate to find an alternative that might work better for everyone. You may also consider using Scrum Values as guidance in this context.

3. Use data

Simply, if you believe that your stress predominantly comes from organisational dysfunctionalities and external pressure, make it transparent for decision-makers and whoever has an interest in the result of the work you do.

Reveal and discuss how it affects mental health, quality of work, time to market, sustainability, innovation, and the company's reputation.

As an example, some teams I supported used an interruption board on which they registered the number of times/hours each member was dragged to help someone outside the team about something not related to their Sprint Goal. Then they discussed the findings during the Sprint Retrospective to take actions and have required conversations outside the team as needed.

4. Get help from your Scrum Master

Ask your Scrum Master (or if you know someone else with similar accountability in your organisation) to support you and other people who suffer from similar issues. An experienced and talented change agent will add great value in revealing the sources of stress and improving the situation.

Conclusion

As Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a Lebanese-American scholar and mathematical statistician, once said:

“The ancients knew very well that the only way to understand events was to cause them”

Run some experiments, see what causes a positive change, what makes you feel more engaged, and maybe complaining less =)

In my experience, you can start your experiment by considering the aforementioned approaches, which basically are recognising the sources of stress, accepting your limits, using professionalism as a compass, using data and getting help from an experienced change agent.

If you want to discuss further and/or have a chat about this topic please feel free to contact: sahin@vaxmo.co.uk